Even as his rock fame blossomed in the mid-70s, Bowie periodically challenged audiences with his avant-garde film tastes. The 1976 Isolar tour, which introduced the singer’s glacially aloof ‘Thin White Duke’ persona, opened with a screening of the revolutionary silent short Un chien andalou (1929), a collaboration between director Luis Buñuel and artist Salvador Dalí that is full of surreal nightmare imagery, including a notorious eye-slicing shot.

The Isolar tour’s starkly lit monochrome stage design borrowed from another of Bowie’s enduring cinematic obsessions, German expressionism. After first seeing Robert Weine’s classic silent horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) as an impressionable teenager, Bowie developed a lifelong passion for the expressionist painters and filmmakers that flourished in Germany’s prewar Weimar Republic.

‘He never forgot Dr. Caligari,’ critic and author Paul Morley wrote in a 2016 Guardian essay on Bowie’s silent-age roots. ‘The mysterious, menacing Carnival man, the drunkenly askew streets and buildings, the make-up of the sleepwalking fortune teller, the unnerving predictions of death.’ Flashbacks to Caligari, Morley wrote, ‘would occur for the rest of his life, represented through the mutant characters he played, the art and entertainment he designed and enacted, the unconventional life he lived. He never escaped their shadows, and the light they threw on the darkness of the mind.’

Stephen Dalton, bfi.org.uk, 5 January 2022

Historically, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari can fairly be reckoned as the beginning of German Expressionist cinema. In terms of the gothic – the potent blend of horror and romance with intent to thrill – it represents only a milestone in a vigorous early century revival of a genre which had somewhat faded since the romantic era. Three seminal manifestations of the new gothic were British: Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) and W.W. Jacobs’s The Monkey’s Paw (1902), all of which have captivated filmmakers ever since. The ghost stories of M.R. James began to appear in 1904, those of Algernon Blackwood in 1906. Gaston Leroux wrote Le Mystère de la chambre jaune – the first of several adventures of Detective Rouletabille – in 1907 and The Phantom of the Opera in 1911. Most influential for German cinema, however, were the novels and stories of Hanns Heinz Ewers (1871-1943), later to be notorious as the biographer of Horst Wessel, who portrayed himself in the hero of the Frank Braun gothic trilogy (Der Zauberlehrling, Alraune and Vampir).

Before Caligari, German filmmakers had already seized on the new gothic. The first version of The Phantom of the Opera was directed by the young dancer-choreographer and Reinhardt collaborator Ernst Matray in 1916. The Picture of Dorian Gray was filmed seven times between 1910 and 1918, in Denmark, Russia, Hungary and America, as well as in Germany, where it was directed by Richard Oswald. The Student of Prague, freely adapted by Ewers from Poe’s William Wilson, was filmed by Paul Wegener and Stellan Rye in 1913; Ewers’s own Der unsichtbare Mensch (The Invisible Man) was filmed in 1916, and the scandalous Alraune – frequently to be adapted in later years – in 1918. Old Jewish myth gave Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen a gothic theme for Der Golem (1915). In Britain the first of at least ten adaptations of The Monkey’s Paw appeared in 1915. America seemed slower to feel the new mood, but turned back to an earlier era with two adaptations of Frankenstein, in 1910 (Edison) and in 1915 (Joseph W. Sunley’s Life without Soul).

The marriage of gothic and Expressionism achieved by Caligari was nevertheless a major step for cinema, even if some critics have echoed Blaise Cendrars’s complaint that it ‘casts discredit on modern Art because the discipline of modern painters (Cubist) is not the hyper sensibility of madmen but equilibrium, intensity and mental geometry.’ It is a criticism that fails to recognise that filmmakers were influenced by Expressionist theatre rather than the pure plastic arts of Expressionism which the theatre had borrowed and processed to suit its own forms and purposes. Karlheinz Martin’s Von Morgens bis Mitternacht (1920) was in fact directly based on the stage production of George Kaiser’s Expressionist play. Robert Wiene made three more films in the Expressionist manner, Genuine (1925) and the more successful Raskolnikov (1923) and Orlacs Hände (1925). Other significant titles that belong to the new gothic-Expressionist school were Nosferatu (1921), Murnau’s unauthorised interpretation of Dracula, Fritz Lang’s Destiny (1921), Arthur Robison’s Warning Shadows (1923), Paul Leni’s Waxworks and Henrik Galeen’s The Student of Prague (1926). An intriguing title from the group now lost is Das Haus des Dr. Gaudeamus (1921), co-written by Thea von Harbou, based on her novel Haus ohne Tür und Fenster, and directed by the multi-talented Friedrich Feher, who plays Franz in Caligari.

Viewed afresh, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari remains, after nearly a century, a staggeringly effective film. Very few feature-length films of its period are so compellingly watchable. It makes a dazzling merit of its tiny stage and shoestring budget, thanks to its crazy cubist/expressionist decors, and the impudence of the spinning umbrellas which masquerade as a fairground and the descending flight of steps which magically conveys us there from the city. The story is economically told, with its own jagged rhythm and coherent performances. The painted landscapes, the menacing Caligari and the uncanny Cesare – vanishing into his own shadow; agonisingly, mesmerisingly opening the great enchanted eyes – have bequeathed some of the most haunting images of the gothic cinema.

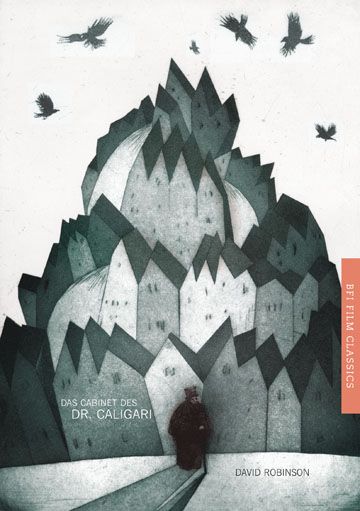

Extracted from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari by David Robinson (BFI Film Classics, 2nd edition, 2013). Reproduced by kind permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. ©David Robinson

UN CHIEN ANDALOU

Director: Luis Buñuel

Production Company: Luis Buñuel

Producers: Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí

Screenplay: Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí

Director of Photography: Albert Duverger

Editor: Luis Buñuel

Sets: Pierre Schildknecht

Cast

Simone Mareuil (the girl)

Pierre Batcheff (the man)

Jaime Miravilles

Salvador Dalí

Luis Buñuel

Jeanne Rucar

France 1928

16 mins

THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI

(DAS CABINET DES DR. CALIGARI)

Director: Robert Wiene

Production Company: Decla Filmgesellschaft

Production: Erich Pommer, Rudolf Meinert

Assistant Director: Rochus Gliese

Scenario: Carl Mayer, Hans Janowitz

Original Story: Hans Janowitz

Director of Photography: Willy Hameister

Art Directors: Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann, Walter Röhrig

Costumes: Walter Reimann

Score Produced by: Studio for Filmmusik der Hochschule für Musik Freiburg i. Br

Direction and Musical Guidance: Sven Thomas Kiebler

Artistic Guidance: Cornelius Schwehr

Music: Pablo Beltrán, Martin Bergande, Carlos Cárdenas, Stephan Dick,

Vasiliki Kourti-Papamoustou, Hong Ting Lai, Seongmin Lee, Cornelius Schwehr,

Carlo Philipp Thomsen

Clarinets: Daniela Kohler, Anri Nishiyama, Hannah Seebauer

Trumpets: Gloria Aurbacher, Lukas Fischer, Fabien Müller

Trombones: Fabian Grabert, Jonathan Riskilly, Johann Schilf, Karoline Stängle

Percussion: Li-Ting Chiu, Teresa Grebtschenko, Jerôme Lepetit

Barrel Organ: Achim Schneider

Pianos: Hazel Beh, Damian Glätzer, Sylvia Loh

Violins: Nitzan Bartana, Hsu-Mo Chien, Sunhee Moon, Shio Ohshita

Violoncellos: Andreas Köhler, Gaby Schumacher, Marlena Schillinger

Contrabass: Juliane Bruckmann, Lutz Gertler, Martina Higuera López

Cast

Werner Krauss (Dr Caligari/director of asylum)

Conrad Veidt (Cesare)

Lil Dagover (Jane)

Friedrich Feher (Franzis)

Hans Heinz von Twardowski (Alan)

Rudolf Lettinger (Dr Olsen)

Ludwig Rex (a rogue)

Elsa Wagner (landlady)

Rudolf Klein-Rogge (captured murderer)

Henri Peters-Arnolds

Hans Lanser-Ludolff

Germany 1920

77 mins

+ Inside Cinema: David Bowie (Sat 15 Jan only)

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari by David Robinson is available from the BFI Shop: https://shop.bfi.org.uk/das-cabinet-des-dr-caligari-bfi-film-classics.html

HOOKED TO THE SILVER SCREEN: BOWIE AT THE MOVIES

2001: A Space Odyssey

Sat 1 Jan 14:20, Sun 23 Jan 18:00, Wed 26 Jan 14:00, 17:30 (IMAX)

Metropolis

Sun 2 Jan 12:00, Tue 4 Jan 14:30, Sun 30 Jan 12:00 (with live piano accompaniment)

A Clockwork Orange

Mon 3 Jan 13:10, Wed 12 Jan 20:25, Sun 23 Jan 15:00, Wed 26 Jan 20:40 (IMAX)

Querelle

Tue 4 Jan 20:20, Tue 18 Jan 18:00

Taxi Driver

Fri 7 Jan 18:00, Sun 16 Jan 18:20, Thu 27 Jan 20:45

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari) + Un chien andalou

Sat 15 Jan 12:30 (+ Inside Cinema: David Bowie), Sat 22 Jan 15:15

In association with

Promotional partner

BFI SOUTHBANK

Welcome to the home of great film and TV, with three cinemas and a studio, a world-class library, regular exhibitions and a pioneering Mediatheque with 1000s of free titles for you to explore. Browse special-edition merchandise in the BFI Shop. We’re also pleased to offer you a unique new space, the BFI Riverfront – with unrivalled riverside views of Waterloo Bridge and beyond, a delicious seasonal menu, plus a stylish balcony bar for cocktails or special events. Come and enjoy a pre-cinema dinner or a drink on the balcony as the sun goes down.

BECOME A BFI MEMBER

Enjoy a great package of film benefits including priority booking at BFI Southbank and BFI Festivals. Join today at bfi.org.uk/join

BFI PLAYER

We are always open online on BFI Player where you can watch the best new, cult & classic cinema on demand. Showcasing hand-picked landmark British and independent titles, films are available to watch in three distinct ways: Subscription, Rentals & Free to view.

See something different today on player.bfi.org.uk

Join the BFI mailing list for regular programme updates. Not yet registered? Create a new account at www.bfi.org.uk/signup

Programme notes and credits compiled by the BFI Documentation Unit

Notes may be edited or abridged

Questions/comments? Contact the Programme Notes team by email