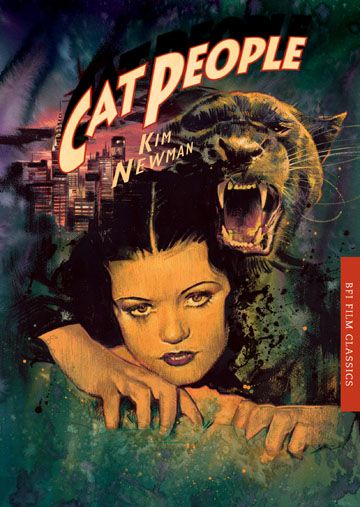

Everyone agrees that the title came first: Cat People.

In March 1942, Russian-born Val Lewton – formerly a pulp novelist, pornographer, publicist, story editor and second-unit producer – left a job with independent David O. Selznick and joined RKO Pictures as a producer. RKO had taken something of a pasting in Hollywood for their sponsorship of Orson Welles, which had led to the astonishing but financially unrewarding Citizen Kane (1941). Replacing vice-president in charge of production George Schaefer, who had brought Welles aboard, was Charles Koerner, who came over from the exhibition side of the business and was charged with executing the studio’s new-minted policy of ‘showmanship, not genius.’

At RKO, Lewton began assembling a team, depending heavily on his contacts from the Selznick organisation: director Jacques Tourneur, with whom he had worked on the second unit of A Tale of Two Cities (1935), and writer DeWitt Bodeen, who had been a research assistant to Aldous Huxley on a Jane Eyre script that eventually became the 1944 film with Joan Fontaine and Orson Welles. They tell slightly different stories of how Cat People came to be. According to Tourneur, ‘Val Lewton called me up at RKO one day and said “Jacques, I’m going to produce a new picture here, and I’d like you to direct it.” He said, “The head of the studio, Charles Koerner, was at a party last night and somebody suggested to him, ‘Why don’t you make a picture called Cat People?’ And Charlie Koerner said to Lewton, “I thought about it all night and it kind of bothered me.” So he called in Lewton and asked him to make the picture. Tourneur later added ‘Val said: “I don’t know what to do.” It was a stupid title and Val, with his good taste, said that the only way to do it was not to make the blood-and-thunder cheap horror movie that the studio expected but something intelligent and in good taste.’

Bodeen’s version is that ‘Val departed for RKO two weeks before I’d finished my work at Selznick’s, and when I phoned him, as I had promised, he quickly made arrangements for me to be hired at RKO as a contract writer at the Guild minimum, which was then $75 a week. When I reported for work, he ran off for me some US and British horror and suspense movies which were typical of what he did not want to do. We spent several days talking about subjects for the first script. Mr Koerner, who had personally welcomed me on my first day at the studio, was of the opinion that vampires, werewolves and manmade monsters had been over-exploited and that “nobody has done much with cats.” He added that he had successfully audience-tested a title he considered highly exploitable – Cat People. “Let’s see what you can do with that,” he ordered. When we were back in his office, Val looked at me glumly and said: “There’s no helping it – we’re stuck with that title. If you want to get out now, I won’t hold it against you.”

The oddest thing Bodeen, Tourneur and all Lewton commentators insist on is a contempt for the title. Bodeen has Lewton in despair giving him a chance to walk away from such an absurdly-titled project while Tourneur – whose credits at the time included Nick Carter, Master Detective (1939), Phantom Raiders (1940) and Doctors Don’t Tell (1941) – simply sneers at such a ‘stupid title’. What, pray, was a cat/werewolf horror movie supposed to be called? Remembrance of Things Past? Cat People seems a simple, evocative, eerie title rather than a 1942 precursor to Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster (1965), Blood Orgy of the She Devils (1973) or Stuff Stephanie in the Incinerator (1989). It marks out its territory perfectly, affords both a literal and a metaphoric reading (it’s not called The Cat Woman) and has a resonance that remains 60 years on.

Cat People is not – though many commentators have said it is or ought to be – a respectable psychological study of a woman with a neurosis; Cat People is a horror film about a woman who turns into a panther. Too much writing about Val Lewton is embarrassed that such a tasteful man should have made horror pictures, and many of the anecdotes about its making suggest some tension between a philistine front office eager for a lurid cat werewolf movie and a daring band of filmmakers intent on slipping them a serious film about psychiatry instead. Lewton himself made his intentions clear in his early notes about the character of Dr Judd, whom he planned as:

‘A man, possibly a doctor, who always gives the scientific or factual explanations for any phenomena that occur, brushing the supernatural aside, and yet, who is always proved wrong by the events on the screen. This device, I hope, will express the audiences’ doubts even before they are fully formulated in their minds and quickly answer them, thus lending a degree of credibility to the yarn, which is going to be difficult to achieve.’

The innovation of Cat People was not ambiguity – which often in horror films serves merely as a respectable get-out clause, allowing audiences who don’t recognise the validity of supernatural stories to read fantastical events as symptoms of a deranged mind (cf., The Innocents, 1961) – but subtlety. Lewton decreed:

‘We tossed away the horror formula right from the beginning. No grisly stuff for us. No mask-like faces hardly human, with gnashing teeth and hair standing on end. No creaking physical manifestations. No horror piled on horror. You can’t keep up horror that’s long sustained. It becomes something to laugh at. But take a sweet love story, or a story of sexual antagonisms, about people like the rest of us, not freaks, and cut in your horror here and there by suggestion, and you’ve got something. Anyhow, we think you have. That’s the way to do it.’

For Lewton, the special-effects lycanthropy of The Wolf Man simply wasn’t frightening enough, and the domestication of the Universal Monsters into well-loved children’s figures suggests that he was right. Though Irena never sports yak-hair and fangs, Cat People is unambiguous about her status: the film’s last line (‘she never lied to us’), along with details like transforming footprints and a shredded bathrobe, prove that Irena really is a Cat Person: Dr Judd interprets what she tells him as a childhood trauma, but we are supposed to understand what really happened before Irena was born: her father made love to her mother in the forest, impregnating her, and she transformed into a panther and killed him. The lesson is not that a psychological study is more worthy than a cat werewolf movie, but that a horror film can have psychological depth. That Irena is a cat person doesn’t make the film any less affecting as the story of a troubled marriage.

Extracted from Cat People by Kim Newman (BFI Film Classics, 1999). Reproduced by kind permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. ©Kim Newman

CAT PEOPLE

Directed by: Jacques Tourneur

Production Company: RKO Radio Pictures

Produced by: Val Lewton

Assistant Director: Doran Cox

Screenplay: DeWitt Bodeen

Story: DeWitt Bodeen, Val Lewton

Director of Photography: Nicholas Musuraca

Edited by: Mark Robson

Art Directors: Albert S. D’Agostino, Walter E. Keller

Set Decorations: Darrell Silvera, Al Fields

Gowns by: Renié

Music by: Roy Webb

Musical Director: C. Bakaleinikoff

Orchestrations: Leonid Raab, John Leipold

Recorded by: John L. Cass

uncredited crew

Supervisor: Lou Ostrow

Dialogue Director: DeWitt Bodeen

Photographic Effects: Vernon L. Walker, Linwood G. Dunn

Assistant Editor: Robert Aldrich

Russian Lyrics: Andrey Tolstoy

Animal Trainer: Mel Koontz

Cast

Simone Simon (Irena Dubrovna Reed)

Kent Smith (Oliver Reed)

Tom Conway (Dr Louis Judd)

Jane Randolph (Alice Moore)

Jack Holt (‘Commodore’ C.R. Cooper)

uncredited cast

Steve Soldi (organ grinder)

Alan Napier (‘Doc’ Carver)

John Piffle (The Belgrade proprietor)

Elizabeth Dunne (Miss Plunkett)

Elizabeth Russell (cat woman)

Alec Craig (zoo keeper)

Dot Farley (Mrs Agnew, concierge)

Theresa Harris (Minnie, waitress)

Charles Jordan (bus driver)

Murdock MacQuarrie (shepherd)

Donald Kerr (taxi driver)

Mary Halsey (blonde swimming pool clerk)

Betty Roadman (Mrs Hansen)

Eddie Dew (street policeman)

Terry Walker (hotel attendant)

Connie Leon (woman)

Henrietta Burnside (second woman)

Dynamite (panther)

Dorothy Lloyd (cat voice)

USA 1943©

73 mins

*Uncredited

Print preserved by Library of Congress

The screening on Mon 19 Dec will be introduced by Clarisse Loughrey, chief film critic for The Independent

Cat People by Kim Newman is available to buy from the BFI Shop: https://shop.bfi.org.uk/cat-people-bfi-film-classics.html

IN DREAMS ARE MONSTERS

The Uninvited

Thu 1 Dec 18:05; Sat 17 Dec 14:30 (+ intro by broadcaster and writer, Louise Blain)

Kwaidan (Kaidan)

Thu 1 Dec 20:00; Tue 13 Dec 17:40

Night of the Eagle

Fri 2 Dec 21:00; Sat 10 Dec 12:10

Daughters of Darkness (Les lèvres rouges)

Sat 3 Dec 20:45: Tue 13 Dec 21:00

Transness in Horror

Tue 6 Dec 18:20

Let the Right One In (Låt den rätte komma in)

Tue 6 Dec 20:45; Thu 22 Dec 18:15

Philosophical Screens: The Lure

Wed 7 Dec 20:10 Blue Room

The Lure (Córki dancing)

Wed 7 Dec 18:15; Thu 22 Dec 20:45 (+ intro by Dr Catherine Wheatley, Reader in Film Studies at King’s College London)

Cat People

Wed 7 Dec 20:50; Mon 19 Dec (+ intro by Clarisse Loughrey, chief film critic for The Independent)

Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio)

Fri 9 Dec 21:00; Sun 18 Dec 18:30

Ring (Ringu)

Sat 10 Dec 20:40; Tue 13 Dec 21:05; Tue 20 Dec 21:00

Atlantics (Atlantique) + Atlantiques

Sun 11 Dec 14:50; Tue 27 Dec 18:20

Sugar Hill

Sun 11 Dec 18:00; Sat 17 Dec 20:40

Häxan

Mon 12 Dec 18:10 (+ live score by The Begotten); Sat 17 Dec 11:45 (with live piano accompaniment)

Sweetheart

Mon 12 Dec 21:00; Tue 27 Dec 12:40

Arrebato

Wed 14 Dec 20:30 (+ intro by writer and broadcaster Anna Bogutskaya); Fri 23 Dec 18:05

The Final Girls LIVE

Thu 15 Dec 20:30

One Cut of the Dead (Kamera o tomeru na!)

Fri 16 Dec 18:15; Fri 30 Dec 20:45

The Fog

Fri 16 Dec 21:00; Wed 28 Dec 18:10

Being Human + Q&A with Toby Whithouse and guests (tbc)

Sat 17 Dec 18:00

Day of the Dead

Mon 19 Dec 20:40; Thu 29 Dec 18:20

Society

Tue 20 Dec 18:15; Wed 28 Dec 20:50

Interview with the Vampire

Wed 21 Dec 18:10: Thu 29 Dec 20:40

Ginger Snaps

Wed 21 Dec 20:50; Tue 27 Dec 15:10

A Dark Song

Fri 23 Dec 20:45; Fri 30 Dec 18:20

City Lit at BFI: Screen Horrors – Screen Monsters

Thu 20 Oct – Thu 15 Dec 18:30–20:30 Studio

BFI SOUTHBANK

Welcome to the home of great film and TV, with three cinemas and a studio, a world-class library, regular exhibitions and a pioneering Mediatheque with 1000s of free titles for you to explore. Browse special-edition merchandise in the BFI Shop.We're also pleased to offer you a unique new space, the BFI Riverfront – with unrivalled riverside views of Waterloo Bridge and beyond, a delicious seasonal menu, plus a stylish balcony bar for cocktails or special events. Come and enjoy a pre-cinema dinner or a drink on the balcony as the sun goes down.

BECOME A BFI MEMBER

Enjoy a great package of film benefits including priority booking at BFI Southbank and BFI Festivals. Join today at bfi.org.uk/join

BFI PLAYER

We are always open online on BFI Player where you can watch the best new, cult & classic cinema on demand. Showcasing hand-picked landmark British and independent titles, films are available to watch in three distinct ways: Subscription, Rentals & Free to view.

See something different today on player.bfi.org.uk

Join the BFI mailing list for regular programme updates. Not yet registered? Create a new account at www.bfi.org.uk/signup

Programme notes and credits compiled by the BFI Documentation Unit

Notes may be edited or abridged

Questions/comments? Contact the Programme Notes team by email