SPOILER WARNING The following notes give away some of the plot.

With titles such as Dead or Alive (1999), Audition (2000), City of Lost Souls and Visitor Q (both 2001), the controversial Japanese cult director Takashi Miike crafted a series of blood-and-guts classics that have provoked outrage for their OTT scenes of SFX splatter and scenarios of prolonged sexual violence. To his detractors, Miike exposes the very worst excesses of the gun-crazed, unrelenting misogyny haunting Japanese culture, while his defenders see these works as uncompromising and experimental comments on the customs of an increasingly techno-alienated society.

Despite its standout grotesque moments, the narrative of Ichi the Killer owes more to the excesses of comic-strip and gangland yakuza culture than to gross-out cinema traditions. In this respect, the extremes of punishment meted out to the film’s females are not only equalled, but exceeded by the representations of male-on-male violence that populate the narrative.

As with other significant entries in Miike’s filmography, it is the repressive and distorted influence of the family unit (both domestic and criminal) that remains one of the pivotal concerns in these unconventional productions. Discussing the familial basis to the regimes of punishment shown in his films, Miike has himself confirmed in interview that: ‘My interest is definitely in the family. Violence may appear to be a particular problem, but my interest is more in human actions and human emotions within the family. But violence of course, as a filmmaker, is an easy tool for expressing or conveying certain problems or emotions that are at work within the family.’

Arguably, the complex web of human affiliations and tensions that these family structures evoke, betrays an emotional intensity in Miike’s work that defies the simplistic label of genre director. This complexity also extends to the narrative and stylistic constructions of the director’s work, which often privileges experimental constructions of time and space associated with European arthouse and avant-garde masters. It is this unconventional mixture of experimental style with extended scenes of violence and suffering that makes Ichi the Killer both innovative and uncomfortable viewing, while confirming Takashi Miike as one of Japan’s most creative and confrontational cult icons of recent decades.

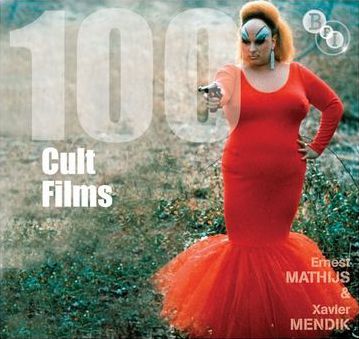

Extracted from 100 Cult Films by Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik (BFI Screen Guides, 2011). Reproduced by kind permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. ©Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik

A contemporary review

The BBFC has passed Ichi the Killer with far fewer cuts than any previous administration would have made, but its extensive trims (all involving ultra-violence, of course, most of it against women) none the less deprive the film of some of its power. The 128-minute uncut version (screened in the London Film Festival and soon to appear on an unrated DVD in the US) has several images which invariably elicit loud moans of disbelief from audiences, and the film needs those moments of outrage as much as Bataille’s Histoire de l’oeil needs its blasphemous, eye-gouging climax. If it doesn’t reduce the viewer to quivering jelly, it’s not doing its job. The UK version may be strong enough to fell first-timers, but anyone who has seen the integral version is bound to find this slightly tame.

Takashi Miike calibrated the film’s outrage factor very precisely as he was forced to tone down or omit many of the original manga’s most extreme climaxes. The 33-year-old Hideo Yamamoto (no relation to the film’s cinematographer, who just happens to have the same name) published the original as a serial in the manga magazine Weekly Young Sunday in 2001, and it was immediately collected in a ten-volume anthology. It contains numerous images of male sexual excitement which are essentially unfilmable, at least as live action. To give just one example, in the original Kakihara unequivocally dies at Ichi’s hands after a razor slash has stripped him of all his clothes and the bondage rig he wears beneath them and bisected his over-excited phallus lengthwise. Of course, questions of feasibility aside, Miike was also constrained by Japan’s own censorship code, which permits all imaginable acts of sex and violence in any combination but still quaintly prohibits the exposure of genitals in a sexual context.

Working for the first time with the absurdist writer Sakichi Sato (they have since teamed up again on the slow-burn yakuza ghost story Gozu), Miike has remained remarkably faithful to the letter of Yamamoto’s manga while pushing its implications into a different (and more sophisticated) direction. The manga is essentially a red-light-district gang-war vignette, garnished with ultra-violent fantasies about what really turns men on. It has a rather banal cyclical structure, ending with a coda showing the boy Takeshi growing up to become the new Ichi and the cycle beginning again. From this Miike and Sato have extrapolated the storyline, many specific episodes and the general tone of jet-black comedy, but they have completely rethought the ending to play up the existential and metaphysical dimensions. The film is less a gang-war thriller than an exploration of the implications of twinning.

Here the ultra-masochist Kakihara and cry-baby killer Ichi are explicitly doppelgangers. Ichi, the ordinary boy with ordinary sexual inhibitions, becomes under hypnosis the super-hero killer (to kill he wears black-leather body armour with a large yellow ‘I’ Ichi on the back) whose acts of extreme violence provide a painful sexual release. Kakihara, whose unrecounted history has taken him so far beyond conventional sexual satisfaction that he’s on a different page entirely, seeks the ultra-sadist who can take him out on the ultimate high. Kakihara imagines that Ichi is his man, only to be confronted with a mirror image of his own pathology: ultra-sadism masking ultra-masochism. Their final confrontation is thus necessarily metaphorical and unresolved. The film’s Kakihara in effect gives himself an auto-erotic climax by spiking his own brain through both ears, and then fantasises the attack by Ichi which finishes him off. Miike consolidates the ambiguity by providing a final image of Kakihara still apparently alive. Then a crow (substituting for the manga’s sentimental dove) takes us past the corpse of Jijii (who has evidently hanged himself) to an anonymous boy in the crowd, whose fleeting gaze at the camera suggests with superb economy that anyone can be an Ichi.

Never one to let metaphysics get in the way of visceral provocation, Miike films this as a live-action cartoon, complete with gleefully cheesy CGI effects. For obvious reasons it’s not really an actors’ film, but it would add up to less than it does without the heroic contributions of an extraordinary cast, which includes the directors Shinya Tsukamoto and Sabu. Japan’s indie star of the moment, Tadanobu Asano, often wasted in passive and reactive roles, here rises to the real challenge of a seemingly unplayable part. His Kakihara, decked out in the yakuza version of glam-rock costumes as he carves his way through all available male and female flesh, is one of cinema’s greatest monsters.

Tony Rayns, Sight & Sound, August 2003

ICHI THE KILLER (KOROSHIYA 1)

Director: Takashi Miike

©: Hideo Yamamoto, Shogakukan Inc, ‘Ichi the Killer’ Production Committee

Presented by: Omega Project, Omega Micott

In co-production with: EMG Distribution, Starmax, Spike, Alpha Group

In association with: Excellent Films

Executive Producers: Albert Yeung Sau-shing, Toyoyuki Yokohama, Sumiji Miyake

Producers: Dai Miyazaki, Akiko Funatsu

Co-producers: Elliot Tong, Yuchul Cho

Associate Producer: Toshiki Kimura

Casting: Mitsuyo Ishigaki

Screenplay: Sakichi Sato

Based on the Weekly Young Sunday comics by: Hideo Yamamoto

Director of Photography: Hideo Yamamoto

Visual Effects Supervisor: Misako Saka

Editor: Yashushi Shimamura

Production Designer: Takashi Sasaki

Costume Designer: Michiko Kitamura

Special Make-up: Yuichi Matsu

Music: Karera Musication

Cast

Tadanobu Asano (Kakihara)

Nao Omori (Ichi)

Shinya Tsukamoto (Jijii)

Alien Sun (Karen)

Sabu (Kaneko)

Japan 2001

128 mins

J-HORROR WEEKENDER

Ring (Ringu)

Fri 29 Oct 18:10

Dark Water (Honogurai mizu no soko kara)

Fri 29 Oct 20:30

Cure (Kyua)

Sat 30 Oct 18:00

Pulse (Kairo)

Sat 30 Oct 20:40

Audition (Ôdishon)

Sun 31 Oct 15:20

Ichi the Killer (Koroshiya 1)

Sun 31 Oct 18:00

Supported by

In partnership wtih

With special thanks to

With the kind support of:

Janus Films/The Criterion Collection, Kadokawa Corporation, Kawakita Memorial Film Institute, Kokusai Hoei Co. Ltd, Nikkatsu Corporation, Toei Co. Ltd

100 Cult Films by Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik is available to buy from the BFI Shop: https://shop.bfi.org.uk/100-cult-films.html

BFI SOUTHBANK

Welcome to the home of great film and TV, with three cinemas and a studio, a world-class library, regular exhibitions and a pioneering Mediatheque with 1000s of free titles for you to explore. Browse special-edition merchandise in the BFI Shop.We're also pleased to offer you a unique new space, the BFI Riverfront – with unrivalled riverside views of Waterloo Bridge and beyond, a delicious seasonal menu, plus a stylish balcony bar for cocktails or special events. Come and enjoy a pre-cinema dinner or a drink on the balcony as the sun goes down.

BECOME A BFI MEMBER

Enjoy a great package of film benefits including priority booking at BFI Southbank and BFI Festivals. Join today at bfi.org.uk/join

BFI PLAYER

We are always open online on BFI Player where you can watch the best new, cult & classic cinema on demand. Showcasing hand-picked landmark British and independent titles, films are available to watch in three distinct ways: Subscription, Rentals & Free to view.

See something different today on player.bfi.org.uk

Join the BFI mailing list for regular programme updates. Not yet registered? Create a new account at www.bfi.org.uk/signup

Programme notes and credits compiled by the BFI Documentation Unit

Notes may be edited or abridged

Questions/comments? Contact the Programme Notes team by email