In 1955, the great Japanese film director Akira Kurosawa and his colleagues began work on an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, transposing from medieval Scotland to medieval Japan the tale of a heroic warrior tricked into a violent and ultimately futile usurpation by supernatural prophecies and an ambitious wife. Kurosawa had aspired to undertake this project for many years, but his initial effort was delayed by the release of Orson Welles’ 1948 version – which, with its low-budget Halloween atmospherics and its abortive attempt to mimic medieval Scottish pronunciation, was neither a critical nor a commercial success.

Kurosawa’s version has emerged as a classic both in the world of Shakespeare performances (screened and discussed in countless secondary and university literature courses every year) and in the world of cinema (it was the inaugural screening of the National Film Theatre in London, and was handsomely reissued by Criterion in 2003). The greatness of Throne of Blood – titled Kumonosu-jô, which would be better translated as ‘Spider’s Web Castle’ – was not immediately noticed in Japan. It proved only mildly profitable for the Toho movie studio, which was hoping to catch a share of the booming market for samurai films (in the jidai-geki genre of historical period pieces) while keeping the international art-cinema audience won by Kurosawa’s Rashomon in 1950; and it only tied for fourth place in Kinema Junpô’s influential ranking of the year’s best movies in Japan.

But – in contrast to the tepid domestic response, a contrast that has fuelled charges that Kurosawa abandons Japanese authenticity to please foreign audiences – the impact in the West was remarkable. Although initially laughed off by Bosley Crowther in The New York Times as an ‘odd amalgamation of cultural contrasts’ that inadvertently ‘hits the occidental funnybone’, Kurosawa’s adaptation quickly commanded high and wide respect. The then vast readership of Time magazine was told that Throne of Blood was ‘the most brilliant and original attempt ever made to put Shakespeare in pictures’, an effort for which Kurosawa ‘must be numbered with Sergei Eisenstein and D.W. Griffith among the supreme creators of cinema’. Among notably distinguished directors of the Shakespearean stage and international film, Sir Peter Hall called Throne of Blood ‘perhaps the most successful Shakespeare film ever made’, and Grigori Kozintsev (who made the justly famous Russian King Lear, 1971) called it ‘the finest of Shakespearean movies’. The renowned film theorist Noël Burch, who also wrote what is still probably the most important western study of Japanese film, lauded Throne of Blood as ‘indisputably Kurosawa’s finest achievement’. T.S. Eliot reportedly identified Throne of Blood as his favourite movie – or perhaps just as his favourite Shakespeare movie, or at least as presenting his favourite Lady Macbeth. Harold Bloom’s best-selling study of Shakespeare has praised it as ‘the most successful film version of Macbeth’, and many scholars of Renaissance literature concur.

How could a masterpiece as dependent on its intensely poetic language as Macbeth survive so well its translation into a verbally sparse Japanese film? Although some of Kurosawa’s collaborators have said they did not even read Shakespeare’s play in preparing their screenplay, the director clearly sought out visual parallels to Shakespeare’s specific language, and drew on some large moral and existential ideas that Shakespeare articulates. The dominant theme of this film is the futile struggle of the self against nature. Kurosawa implicitly condemns the doomed battle of human pride and desire against an indifferent universe of overpowering scope, weight and persistence, but also mourns the suffering of the great human spirit tricked into waging that battle. The struggle to pull free of the spider’s web is foolish to undertake, but – and here we may see Kurosawa’s controversial humanistic investment in the individual – at moments heroic, and perhaps inevitable.

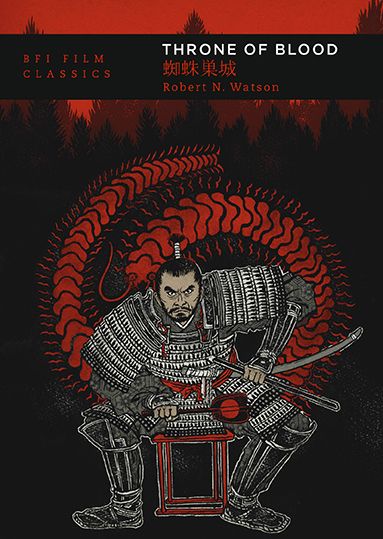

Extracted from Throne of Blood by Robert N. Watson (BFI Film Classics, 2014). Reproduced by kind permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. ©Robert N. Watson

Kurosawa on ‘Throne of Blood’

With this film, The Lower Depths, and The Hidden Fortress, I seem to have made a jidai-geki trilogy. [Almost all Japanese, and Kurosawa is no exception, think of films as being divided into period-pictures (jidai-geki) and modern-story pictures (gendai-mono) as though these were the only two alternatives. The West has something like this in its attitudes toward Westerns (i.e. the ‘adult Western’ etc.) and the crime film.] I have long thought that the Japanese jidai picture is very often historically uninformed, and, beyond this, has never really availed itself of modern filmmaking techniques. In Seven Samurai we tried to do something about that, and Throne of Blood had the same general feeling behind it.

Originally I had wanted to produce this film and let a younger director direct it. But when the script was finished and Toho saw how expensive it would be, they asked me to direct it. So I did – my contract expired after these three films.

I also had another idea about the film, and that was simply that I wanted to make Macbeth. [Kurosawa had seen none of the other film versions, though much later he saw Orson Welles’ on television.] The problem was: how to adapt the story to Japanese thinking. The story is understandable enough but the Japanese tend to think differently about such things as witches and ghosts. [Though ghosts tend to be vengeful, as in the innumerable kaidan films, the idea of a gratuitously malevolent trio of witches is far from the Japanese imagination.] I decided upon the techniques of the Noh, because in Noh style and story are one. I wanted to use the way Noh actors have of moving their bodies, the way they have of walking, and the general composition which the Noh stage provides. [In the film the most successful examples of this are usually associated with ‘Macbeth’s’ wife, who uses slightly accelerated Noh movements, and the scene where she tries to wash her hands clean is pure Noh; also the asymmetrical composition of Noh is much seen, particularly in the long conversation scenes between ‘Macbeth’ and his wife before the initial murder. The appearance of Banquo’s ghost, on the other hand, uses very little Noh technique.]

This is one of the reasons why there are so very few close-ups in the picture. I tried to show everything using the full-shot. Japanese almost never make films in this way and I remember I confused my staff thoroughly with my instructions. They were so used to moving up for moments of emotion, and I told them to move further back. In this way I suppose you could call the film experimental.

It was a very hard film to make. We decided that the main castle set had to be built on the slope of Mount Fuji, not because I wanted to show this mountain but because it has precisely the stunted landscape that I wanted. And it is usually foggy. I had decided I wanted lots of fog for this film. [Kurosawa has said elsewhere that since he was very young the idea of samurai galloping out of the fog much appealed to him. At the beginning of the original version of this film, Mifune and Minoru gallop in and out of the fog eight times.] Also I wanted a low, squat castle. Kohei Ezaki, who was the art director, wanted a towering castle, but I had my way. Making the set was very difficult because we didn’t have enough people and the location was so far from Tokyo. Fortunately, there was a US Marine Corps base nearby and they helped a great deal; also a whole MP battalion helped us out. We all worked very hard indeed, clearing the ground, building the set. Our labour on this steep fog-bound slope, I remember, absolutely exhausted us – we almost got sick.

Akira Kurosawa interviewed by Donald Richie, Sight and Sound, Autumn 1964

THRONE OF BLOOD (KUMONOSU-JÔ)

Director: Akira Kurosawa

©: Toho Co. Ltd.

Production Company: Toho Co. Ltd.

Producers: Akira Kurosawa, Sojiro Motoki

Production Supervisor: Hiroshi Nezu

1st Assistant Directors: Hiromichi Horikawa, Mimachi Norase

2nd Assistant Directors: Yasuyoshi Tajitsu, Michio Yamamoto, Kan Sano

Script Supervisor: Teruyo Nogami

Screenplay: Hideo Oguni, Shinobu Hashimoto, Ryuzo Kikushima, Akira Kurosawa

Based on the play Macbeth by: William Shakespeare

Director of Photography: Asaichi Nakai

Lighting: Kuichiro Kishida

Camera Assistant: Takao Saito

Stills Photography: Masao Fukuda

Editor: Chozo Obata

Art Supervision: Kohei Ezaki

Art Director: Yoshiro Muraki

Assistant Art Director: Yoshifumi Honda

Properties: Koichi Hamamura

Hair: Yoshiko Matsumoto, Junjiro Yamada

Music: Masaru Sato

Sound Recording: Fumio Yanoguchi

Sound Effects: Ichiro Minawa

Cast

Toshiro Mifune (Taketoki Washizu)

Isuzu Yamada (Asaji, his wife)

Takashi Shimura (Noriyasu Odagura)

Minoru Chiaki (Yoshiaki Miki)

Akira Kubo (Yoshiteru Miki, his son)

Takamaru Sasaki (Kuniharu Tsuzuki)

Yôichi Tachikawa (Kunimaru Tsuzuki, his son)

Chieko Naniwa (sorceress)

Isao Kimura (phantom soldier)

Eiko Miyoshi (old servant)

Kokuten Kodo (commanding officer)

Seiji Miyaguchi, Nobuo Nakamura (ghosts)

Yoshio Inaba

Gen Shimizu

Yoshio Tsuchiya

Kichijiro Ueda

Nakajiro Tomita

Seijiro Onda

Japan 1957

110 mins

The screenings on Thu 21 Oct and Fri 12 Nov include a screening of Inside Cinema: Akira Kurosawa (2021, 6 mins)

Supported by

In partnership wtih

With special thanks to

With the kind support of:

Janus Films/The Criterion Collection, Kadokawa Corporation, Kawakita Memorial Film Institute, Kokusai Hoei Co. Ltd, Nikkatsu Corporation, Toei Co. Ltd

Throne of Blood (new edition) by Robert N. Watson is available to buy from the BFI Shop: https://shop.bfi.org.uk/pre-order-throne-of-blood-bfi-film-classics.html

BFI SOUTHBANK

Welcome to the home of great film and TV, with three cinemas and a studio, a world-class library, regular exhibitions and a pioneering Mediatheque with 1000s of free titles for you to explore. Browse special-edition merchandise in the BFI Shop.We're also pleased to offer you a unique new space, the BFI Riverfront – with unrivalled riverside views of Waterloo Bridge and beyond, a delicious seasonal menu, plus a stylish balcony bar for cocktails or special events. Come and enjoy a pre-cinema dinner or a drink on the balcony as the sun goes down.

BECOME A BFI MEMBER

Enjoy a great package of film benefits including priority booking at BFI Southbank and BFI Festivals. Join today at bfi.org.uk/join

BFI PLAYER

We are always open online on BFI Player where you can watch the best new, cult & classic cinema on demand. Showcasing hand-picked landmark British and independent titles, films are available to watch in three distinct ways: Subscription, Rentals & Free to view.

See something different today on player.bfi.org.uk

Join the BFI mailing list for regular programme updates. Not yet registered? Create a new account at www.bfi.org.uk/signup

Programme notes and credits compiled by the BFI Documentation Unit

Notes may be edited or abridged

Questions/comments? Contact the Programme Notes team by email