When John Carpenter’s The Thing was unleashed into cinemas in 1982, it received an almost unanimous critical drubbing on both sides of the Atlantic. Critic after critic griped about weak characterisation, lack of tension, and sacrifice of the film’s mood and structure to the stomach-turning special effects. More than one reviewer dismissed it glibly but not very accurately as ‘Alien on ice’. The consensus was that Carpenter’s The Thing couldn’t – as Rolling Stone put it – ‘hold a candle to Howard Hawks’ trailblazing 1951 classic The Thing from Another World’.

One or two brave souls swam against the critical tide. Alan Frank in the Daily Star maintained ‘You won’t find a better spine-chiller than The Thing,’ while Richard Cook in New Musical Express remarked on its ‘sense of fatality’, praised Carpenter’s ‘manipulation of the confining qualities of film’, and declared that it set ‘the standard by which all creature thrillers will have to be judged’.

But The Thing went belly-up at the box-office, and not just because of the overwhelming blanket of negative criticism. Just as likely to have been a factor was the prevailing mood of the times. In 1982, the political philosophies of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were filtering through to the masses, resulting in an overall feeling a long way from John Carpenter’s ironic, subversive, anti-authoritarian tone. Even in the 80s, Carpenter’s films evinced a cynical sensibility more in tune with the innovative, iconoclastic 70s, with their conspiracy theories and downbeat endings, than with the Mammon-worshipping workaholism of the yuppie decade.

Even more damaging, from The Thing’s point of view, was the arrival on the scene of a small, prune-like creature with an elongated neck, enormous eyes and magic finger. Audiences weren’t keen on the idea of a space monster which did unpleasant things to the human body. They preferred an alien equivalent of the teddy-bear and wanted reassurance that, if there were something out there, it would be benign. They also wanted the promise of life after death, the comfort of religious undertones, and a heartwarming love story with a sob-into-your-hanky sentimental ending. ‘You must remember the time it [The Thing] was released was the summer of E.T.,’ says John Carpenter. ‘And it was a very bleak and hopeless film. There were no women in the movie, and people thought I went too far.’

When The Thing first came out, I was bowled over by it. I was transfixed by the tension all the critics had maintained was non-existent; the build-up made me so nervous that I thought I would have to leave the cinema even before the first hint of tentacle. I was knocked out by Dean Cundey’s spare yet elegant widescreen cinematography. And I was impressed by the economical but effective performances from a cleverly chosen cast which, together with Bill Lancaster’s deft screenplay, never for one moment left you stranded in limbo, trying to work out which character was which.

I have since watched this film so many times, both on video and on the big screen, that I now know virtually every syllable of Lancaster’s dialogue, every last beat of Ennio Morricone’s haunting music, every conjuring trick of Carpenter’s direction. And yet I can still watch it with pleasure, its tension unimpaired by familiarity. The Thing has carved itself a niche in that small pantheon of films that need to be revisited at regular intervals if I am to preserve my faith in the movies and keep myself sane. It goes on waving its repulsive yet fascinating tentacles in my face. I continue to mull over plot details, wondering which characters have been infected, and when; I brood about the maddening, ambiguous, magnificent ending; and I ponder the philosophical questions: at what point does a human being cease to be a human being and become a Thing? And what would be so awful about being a Thing anyway?

It starts off as it means to go on – a Technicolor film with a predominantly monochrome colour scheme. Later on, there will be vivid eruptions of red, green and yellow gloop, but in the beginning The Thing consists of plain white credits against a black background: black and white – the predominant colour scheme of the film. It’s not so much the black and white of good and evil, as a chess game between two unevenly matched players: a beginner versus a Grandmaster or man versus the Thing, with the Thing making all the best and most unexpected moves.

There’s a single ominous chord on the soundtrack – a chord which gains in intensity.

The black background becomes outer space, sprinkled with the pinpricks of millions of stars. This is the Outer Space Prologue, and though we don’t yet know it, it’s set hundreds of thousands of years ago. Flying past us, hurtling past the camera with frightening force and speed, comes what is unmistakably a flying saucer, apparently out of control. It breaches the earth’s atmosphere with a brief flare-up of brightness, and the title of the film is seared white-hot into the screen with a scorching, rending sound. The logo is identical to that used in The Thing from Another World. The aliens, once again, have landed.

Carpenter was to use another Outer Space Prologue two years later in Starman, a sci-fi love story featuring Jeff Bridges as a benign alien about as far as one could get from the impersonal malevolence of the Thing: the Voyager II space probe, laden with messages of goodwill and launched in 1977, is shown hurtling through space, belting out ‘I Can’t Get No Satisfaction’ by the Rolling Stones. As befits what might be described as Carpenter’s own E.T., the tone here is upbeat and positive, totally lacking in the ominousness of The Thing’s beginning, which was to be echoed more closely in the Outer Space Prologue to the 1996 box-office smash Independence Day, in which the surface of the moon is rippled by the passing of a colossal space craft.

Next, The Thing takes a mighty leap forward in time, to the present – or at least to the present as it was in the year of the film’s release. A subtitle identifies the time and location as ‘ANTARCTIC, WINTER 1982’. The single ominous chord now gives way to the main theme of Ennio Morricone’s simple but insidiously effective soundtrack – a tonic heartbeat overlaid with a repeating two-note figure rising from the dominant 5th to an unsettled and unsettling minor 6th, with a falling sequence beneath it. Carpenter wrote his own synthesizer themes for many of his films, and it’s almost as though Morricone had studied the scores for Assault on Precinct 13, Halloween, The Fog, and so on, and had determined to outdo them in minimalism and menace. The Thing is among his least typical scores – very different from his usual plaintive lyricism – but one of his most effective. The heartbeat at its centre suggests life – but not necessarily life as we would want to know it.

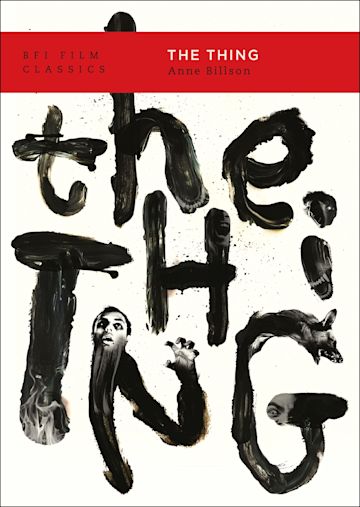

Extracted from The Thing by Anne Billson (BFI Film Classics, 1997).

Reproduced by kind permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. ©Anne Billson

THE THING

Directed by: John Carpenter

©: Universal City Studios, Inc.

a Turman-Foster Company production

a Universal picture

Executive Producer: Wilbur Stark

Produced by: David Foster, Lawrence Turman

Co-producer: Stuart Cohen

Associate Producer: Larry Franco

Production Manager: Robert Latham Brown

Production Accountant: Karen Miller

Production Secretary: Debbie Collier

1st Assistant Director: Larry Franco

2nd Assistant Director: Jeffrey Chernov

Assistant to John Carpenter: Ellen Benjamin

Script Supervisor: Candy Marcellino

Casting by: Anita Dann

Screenplay by: Bill Lancaster

Based on the story ‘Who Goes There?’ by: John W. Campbell Jr

Director of Photography: Dean Cundey

Camera Operator: Raymond Stella

First Assistant Cameraman: Clyde Bryan

Second Assistant Cameraman: Steve Tate

Gaffers: Mark Walthour, Tom Marshall

Electric Best Boy: Charles E. Nippell

Key Grip: Ronald T. Woodward

Best Boy Grip: Laszlo Horvath

Grip: Ray Kinzer

Dolly Grip: Kriss Krosskove

Special Visual Effects by: Albert Whitlock

Matte Photography by: Bill Taylor

Special Effects: Roy Arbogast

Special Effects Assistants: William D. Lee, Hans Metz, John Stirber

Special Effects Foreman: Hal Bigger

Computer Graphics: Motion Graphics

Dimensional Animation Effects Created by: Randall William Cook

Dimensional Animation Effects Crews: James Aupperle, James Belohovek, Ernest D. Farino, Carl Surges

Edited by: Todd Ramsay

Assistant Film Editors: Jan Wesley, Kim Ray

Production Designer: John J. Lloyd

Art Director: Henry Larrecq

Set Decorator: John Dwyer

Leadman: Bart Susman

Property Master: John Zemansky

Propmaker Foreman: Bob Nohles

Painter: James Callan

Costume Supervisors: Ronald I. Caplan, Gilbert Loe

Make-up: Kenneth Chase

Special Make-up Effects Created and Designed by: Rob Bottin

Special Make-up Effects Unit Line Producer: Eric Jensen

Special Make-up Effects Unit Coordinator Mechanical Animation: David Kelsey

Special Make-up Effects Unit Coordinator Special Make-up Effects: Ken Diaz

Special Make-up Effects Unit Production Special Make-up Effects Unit Special Technicians: Gunnar Ferdinansen, Margaret Beserra

Special Wigs: Vivienne Walker, Josephine Turner

End Titles & Optical Effects: Universal Title

Main Title Sequence Visual Effects Designed by: Visual Concept Engineering, Peter Kuran

Visual Concept Engineering Miniature Supervisor: Susan K. Turner

Visual Concept Engineering Animators: Katherine Kean, Keith Tucker

Opticals: RGB Opticals, James Hagedorn, George Lockwood

Filmed in: Panavision

Colour by: Technicolor

Music by: Ennio Morricone

Synthesizer Sound: Craig Harris

Music Editor: Clif Kohlweck

Production Sound: Thomas Causey

Boom Operator: Joe Brennan

Sound Re-recording: Bill Varney, Steve Maslow, Gregg Landaker

Supervising Sound Editors: David Lewis Yewdall, Colin C. Mouat

Sound Editor: Kendrick P. Sweet

Sound Effects Editor: Warren Hamilton Jr

Foley Supervisor: John K. Adams

Stunt Co-ordinator: Dick Warlock

Juneau Technical Adviser: Dr Maynard M. Miller

Animal Trainer: Bob Weatherwax

Cast

Kurt Russell (R.J. MacReady)

A. Wilford Brimley (Blair)

T.K. Carter (Nauls)

David Clennon (Palmer)

Keith David (Childs)

Richard Dysart (Dr Copper)

Charles Hallahan (Norris)

Peter Maloney (Bennings)

Richard Masur (Clark)

Donald Moffat (Captain Garry)

Joel Polis (Fuchs)

Thomas Waites (Windows)

Norbert Weisser (Norwegian)

Larry Franco (Norwegian passenger with rifle)

Nate Irwin (helicopter pilot)

William Zeman (pilot)

John Carpenter (Norwegian in video footage) *

Adrienne Barbeau (voice of computer) *

USA 1982©

109 mins

*Uncredited

The Thing by Anne Billson is available to order from the BFI Shop: https://shop.bfi.org.uk/the-thing-1982-bfi-film-classics-paperback.html

SCALA: SEX, DRUGS AND ROCK AND ROLL CINEMA

Basket Case

Mon 1 Jan 15:20; Thu 25 Jan 20:40

Pink Flamingos

Mon 1 Jan 18:20; Fri 19 Jan 18:20; Fri 26 Jan 20:50 (+ intro by Mark Moore and Tasty Tim)

Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!

Tue 2 Jan 18:20; Thu 18 Jan 21:00 (+ intro by film scholar and writer Virginie Selavy)

Taxi zum Klo

Wed 3 Jan 20:50; Mon 8 Jan 20:40 (+ intro by Vic Roberts, Scala usher)

The Warriors

Sat 6 Jan 18:15; Sun 14 Jan 12:00; Wed 17 Jan 20:55 (+ intro by SCALA!!! co-director Ali Catterall)

Thundercrack!

Sat 6 Jan 20:00; Sun 14 Jan 14:10

The Evil Dead

Fri 5 Jan 20:45 (+ intro by Graham Humphreys, freelance illustrator and designer of the original UK marketing for The Evil Dead); Tue 30 Jan 18:10

Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom

Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma

Tue 9 Jan 20:35 (+ intro by season curator Jason Wood, BFI Executive Director of Public Programmes & Audiences); Tue 23 Jan 18:10

Sight and Sound Presents: Scala Spirit 1993-2023

Thu 11 Jan 18:20

Shivers

Thu 11 Jan 21:00; Sun 21 Jan 15:20

Pee-wee’s Big Adventure

Fri 12 Jan 18:10 (+ intro by Ben Roberts, BFI CEO); Wed 31 Jan 18:20

Pink Narcissus + Un chant d’amour

Fri 12 Jan 20:40; Thu 25 Jan 18:20

The Saint: Teresa + intro by Dick Fiddy, Archive TV Programmer + The Avengers: A Touch of Brimstone

Sat 13 Jan 14:30

Looking for Mr Goodbar + Dick

Sat 13 Jan 17:45 (+ intro by season curator Jane Giles); Mon 22 Jan 20:10

The Thing

Sat 13 Jan 20:40; Mon 29 Jan 20:45

The Beast La Bête

Tue 16 Jan 20:45; Tue 23 Jan 20:50

Surprise Film + intro by season curator Jane Giles

Sat 20 Jan 17:10

A Clockwork Orange

Sun 21 Jan 18:00; Wed 31 Jan 20:25

Shock, Horror! The Scala All-nighter: An American Werewolf in London; The Creature from the Black Lagoon – 3D; Videodrome; The Incredible Shrinking Man; A Nightmare on Elm Street

Sat 27 Jan 22:30 BFI IMAX

SIGHT AND SOUND

Never miss an issue with Sight and Sound, the BFI’s internationally renowned film magazine. Subscribe from just £25*

*Price based on a 6-month print subscription (UK only). More info: sightandsoundsubs.bfi.org.uk

BFI SOUTHBANK

Welcome to the home of great film and TV, with three cinemas and a studio, a world-class library, regular exhibitions and a pioneering Mediatheque with 1000s of free titles for you to explore. Browse special-edition merchandise in the BFI Shop.We're also pleased to offer you a unique new space, the BFI Riverfront – with unrivalled riverside views of Waterloo Bridge and beyond, a delicious seasonal menu, plus a stylish balcony bar for cocktails or special events. Come and enjoy a pre-cinema dinner or a drink on the balcony as the sun goes down.

BECOME A BFI MEMBER

Enjoy a great package of film benefits including priority booking at BFI Southbank and BFI Festivals. Join today at bfi.org.uk/join

BFI PLAYER

We are always open online on BFI Player where you can watch the best new, cult & classic cinema on demand. Showcasing hand-picked landmark British and independent titles, films are available to watch in three distinct ways: Subscription, Rentals & Free to view.

See something different today on player.bfi.org.uk

Join the BFI mailing list for regular programme updates. Not yet registered? Create a new account at www.bfi.org.uk/signup

Programme notes and credits compiled by Sight and Sound and the BFI Documentation Unit

Notes may be edited or abridged

Questions/comments? Contact the Programme Notes team by email