Never do the years pass so sadly on screen as they do in Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sansho Dayu. In this period tragedy set in 11th-century Japan, the reunion of a kidnapped brother and sister with their heartbroken mother seems less and less likely with the escaping decades.

By the time of Sansho Dayu’s release, Mizoguchi was nearing the end of his career, but enjoying a newfound recognition among western critics. They’d discovered Japanese cinema via the triumph of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon at the 1951 Venice Film Festival, and found more pleasures yet in Mizoguchi’s film Ugetsu monogatari, which screened at Venice in 1953.

Though Mizoguchi interspersed these sweeping historical epics with a series of brilliant modern-day dramas, it was the exotic tragedies of Japan’s past that were snapped up by western distributors. For English-speaking critics, Sansho Dayu (known as Sansho the Bailiff in the US) confirmed the promise of Ugetsu monogatari that Mizoguchi was a master of visual storytelling, using flowing camera movements and telescoped years to craft tragedies of almost Shakespearian scope and gravity.

Sixty years have done nothing to diminish the emotional power of the film. It came in at number 59 in Sight & Sound’s 2012 greatest films poll, and few movies have been written about so effusively. Critic Gilbert Adair called it ‘one of those films for whose sake the cinema exists’, while New Yorker reviewer Anthony Lane wrote: ‘I have seen Sansho only once, a decade ago, emerging from the cinema a broken man but calm in my conviction that I had never seen anything better; I have not dared watch it again, reluctant to ruin the spell, but also because the human heart was not designed to weather such an ordeal.’

Samuel Wigley, bfi.org.uk, 15 May 2015

As we read our newsfeeds in the summer of 2019, Sansho Dayu is more relevant than ever. A mother on a dangerous journey to reunite with her exiled husband, her children forcibly taken from her, a callous government complicit in the disruption of her family – the drama at the heart of the film is re-enacted daily by federal officials on the southern border of the United States. There is some historical irony here. When Mizoguchi made Sansho Dayu in 1954 he set the story in an ancient era, far removed from the democratic reforms Japan had newly embraced under the American occupation. The fact that cruelty repeats itself comes as no surprise. What shocks us is the realisation that the current divider of families is the nation that taught the lessons of human rights to the post-war world.

Mizoguchi allegorised the displacements of the Second World War for a Japanese audience who understood themselves, rightly or wrongly, as the victims of militarism. Hardly a family that had survived the war was untouched by it. Fathers, sons and brothers were dead or missing, and those who did return were often absent emotionally forever after. Post-war viewers of Sansho Dayu would have had little difficulty identifying with a family removed in time but similarly broken under a corrupt regime. A deeper allegory may have touched them as well. The comfort women who were forced into sexual slavery by agents of the military in Japanese-occupied territories were no different from Tamaki, played by the most popular actress of her day, Kinuyo Tanaka. Though the issue may not have been prominent in the post-war press, it was a shameful and open secret of experience on the front. Recent trade tensions between Tokyo and Seoul are rooted in decades of disputes over compensation to forced labourers and comfort women. A resurgent neo-nationalism in both countries makes any resolution in the near future unlikely.

Mizoguchi denounced the wrongs of the Japanese military but also put forth the concept of human rights as another name for the Buddhist value of compassion. The film makes clear compassion is not a simple feeling of kindness or sympathy but the active motivation to alleviate the suffering of an unrelated other, without personal gain, and with some risk to oneself. It is an emotion that occurs in a cluster of American and Japanese films set in the Second World War or inspired by its aftermath. One of the earliest, Casablanca (Curtiz, 1942), defines compassionate masculinity in terms of the iconic tough guy Rick. The protagonist of Schindler’s List (Spielberg, 1993) is a similarly charismatic man of power in Nazi-occupied Poland before he sacrifices all to save the lives of Jews. Three post-war works by Kurosawa – Seven Samurai (1954), Ikiru (1952) and High and Low (1963) – centre on the consequences of the choice of compassion for high-status men. As in Sansho Dayu, the hero in each of these stories loses the very thing that matters most to him: the woman he loves, his money, his family, his identity, his position or his life. Compassion is controversial, philosopher Martha Nussbaum tells us, and as these works bring home, not for the faint of heart.

Mizoguchi’s legacy comes full circle in Kore-eda’s 2018 masterpiece Shoplifters (Nambiki kazoku), winner of the Cannes Film Festival Palme d’Or. Its French title is Une affaire de famille and asks the twin questions Mizoguchi posed over 60 years ago: What is a family? And is it jeopardised or strengthened by compassion for those outside it? Neither director has the answers but both share a fear similar to our own when we find ourselves riveted to the latest news of violence on our borders. The family is a microcosm of the nation, these films seem to say, and without governance based on an ethics of compassion, the threat is not outside us but within ourselves.

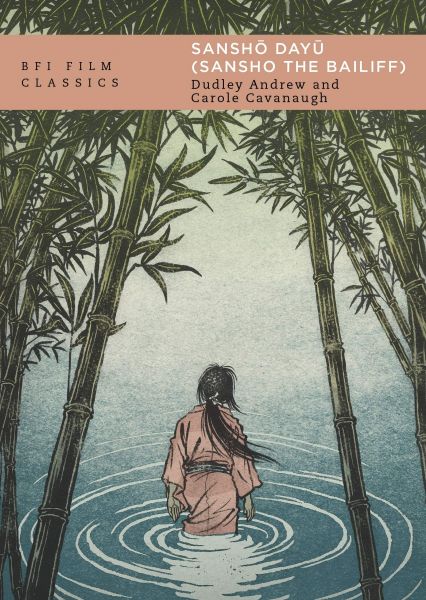

Foreword to the 2020 edition of Sansho Dayu (Dudley Andrew and Carole Cavanaugh, BFI Film Classics). Reproduced by kind permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. ©Dudley Andrew and Carole Cavanaugh

SANSHO THE BAILIFF (SANSHO DAYU)

Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

Production Company: Daiei

Producer: Masaichi Nagata

Production Manager: Masatsugu Hashimoto

Planning: Kyuichi Tsuji

Assistant Director: Tokuzô Tanaka

Screenplay: Yoshikata Yoda, Yahiro Fuji

Based on the novel of the same name by: Ogai Mori

Director of Photography: Kazuo Miyagawa

Lighting: Kenichi Okamoto

Lighting Assistant: Yasuo Iwaki

Assistant Photographer: Shozo Tanaka

Editor: Mitsuzô Miyata

Art Directors: Kisaku Itô, Kozaburô Nakajima

Assistant Art Director: Akira Naitô

Set Decorator: Uichirô Yamamoto

Paintings: Tazaburô Ôta

Architectural Authenticity: Giichi Fujiwara

Costumes: Yoshio Ueno, Yoshima Shima

Make-up: Masanori Kobayashi

Hairstyles: Ritsu Hanai

Music: Fumio Hayasaka

Traditional Music: Kinshichi Kodera, Tamezô Mochizuki

Music Director: Kisaku Mizoguchi

Sound Recording: Iwao Ôtani

Assistant Sound Recording: Kyôichi Emura

Fight Consultant: Shôhei Miyauchi

Cast

Kinuyo Tanaka (Tamaki, Lady Taira, later ‘Nakagimi’)

Yoshiaki Hanayaki (Zushiô, Tamaki’s son, later ‘Mutsu-Waka’)

Kyôko Kagawa (Anju, Tamaki’s daughter, later ‘Shinobu’)

Eitarô Shindô (Sansho the bailiff)

Akitake Kôno (Tarô, Sansho’s son)

Ken Mitsuda (Morozane Fujiwara, prime minister)

Kazukimi Okuni (Norimura, judge)

Masao Shimizu (Masauji Taira, governor of Mutsu)

Shinobu Araki (Sadayû, Masauji’s bailiff)

Shôzô Nanbu (Masasue Taira, Masauji’s uncle)

Chieko Naniwa (Ubatake, Tanaka’s family nurse)

Masahiko Katô (Zushiô as a boy)

Naoki Fujiwara (Zushiô as a child)

Keiko Enami (Anju as a child)

Kikue Môri (Miko, Shinto priestess at Naoe harbour)

Akira Shimizu (slavedealer)

Saburo Date (Kinpei, Sanshô’s head guard)

Bontarô Miyake (Kichiji, Sansho’s guard)

Yôko Kosono (Kohagi, young slave)

Kimiko Tachibana (Namiji, old slave)

Ichiro Sugai (Nio, old slave who tries to escape)

Yukiko Soma (Kayano, slave)

Kanji Koshiba (Kaikudo Naito, finance minister’s envoy)

Ryônosuke Azuma (owner of brothel on Sado)

Yukio Horikita (Jirô of Sado)

Hachirô Ôkuni (Saburo Miyazaki)

Rôsuke Kagawa (Donmô, priest of Nakayama temple)

Jun’nosuke Hayama (old priest)

Kazuyoshi Tamachi (justice of the peace)

Akiyoshi Kikuno (prison guard)

Teruko Omi (new ‘Nakagimi’)

Reiko Kongo (Shiono)

Jun Fujikawa (Kanamaru)

Sôji Shibata (man on Sado)

Sumao Ishiwara (litter bearer)

Ichirô Amano (gatekeeper)

Tokio Oki (man at Naoe harbour)

Midori Komatsu (woman at habour)

Gôro Nakanishi (guard)

Keiko Koyanagi, Kazuko Maeda (prostitutes)

Eiji Ishikura, Akira Shiga, Shirô Osaki (farmers)

Japan 1954

124 mins

Sansho Dayu (new edition) by Dudley Andrew and Carole Cavanaugh is available to buy from the BFI Shop: https://shop.bfi.org.uk/sansho-dayu-sansho-the-bailiff-bfi-film-classics.html

SIGHT AND SOUND GREATEST FILMS OF ALL TIME 2022

The General Sun 1 Jan 12:10; Sun 29 Jan 15:10

The Leopard (Il gattopardo)

Sun 1 Jan 14:10; Thu 5 Jan 18:40; Fri 20 Jan 14:00

Sunset Boulevard

Sun 1 Jan 15:50; Fri 27 Jan 14:30; Mon 30 Jan 17:50

Metropolis

Sun 1 Jan 17:55 (+ intro by Bryony Dixon, BFI Curator); Sun 15 Jan 14:40; Mon 30 Jan 16:30 BFI IMAX

L’avventura (The Adventure)

Sun 1 Jan 18:05; Sun 22 Jan 15:20; Mon 30 Jan 20:15

Touki-Bouki

Mon 2 Jan 13:40; Tue 31 Jan 17:40

The Red Shoes

Mon 2 Jan 13:50; Tue 24 Jan 18:05

Once Upon a Time in the West (C’era una volta il West)

Mon 2 Jan 15:20; Sat 7 Jan 17:15; Sun 15 Jan 16:15 BFI IMAX

Get Out

Mon 2 Jan 18:40; Fri 6 Jan 17:50

Pierrot le Fou

Tue 3 Jan 18:10; Wed 4 Jan 20:30; Thu 19 Jan 20:30

My Neighbour Totoro (Tonari no Totoro)

Tue 3 Jan 18:20; Sun 22 Jan 10:00 BFI IMAX;

Sat 28 Jan 13:40

A Man Escaped (Un Condamné à mort s’est échappé)

Tue 3 Jan 18:30; Sat 28 Jan 20:30

Black Girl (La Noire de…)

Tue 3 Jan 20:30; Thu 12 Jan 18:15 (+ intro)

Ugetsu Monogatari

Tue 3 Jan 20:50; Tue 17 Jan 20:30

Madame de…

Wed 4 Jan 14:30; Fri 20 Jan 18:10 (+ intro by Ruby McGuigan, Cultural Programme Manager)

Yi Yi (A One and a Two…)

Wed 4 Jan 18:40; Sun 22 Jan 14:00 (+ intro by Hyun Jin Cho, Film Programmer, BFI Festivals)

The Shining

Fri 6 Jan 20:10; Tue 10 Jan 20:10; Sat 21 Jan 20:30 BFI IMAX

Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi)

Sat 7 Jan 12:10; Sun 22 Jan 12:30 BFI IMAX

Tropical Malady (Sud pralad)

Sat 7 Jan 13:50; Mon 9 Jan 20:40

Histoire(s) du cinema

Sat 7 Jan 16:30

Blue Velvet

Sat 7 Jan 20:30; Fri 20 Jan 20:35; Tue 24 Jan 21:00 BFI IMAX

Sátántangó

Sun 8 Jan 11:15; Sat 21 Jan 13:30

Celine and Julie Go Boating (Céline et Julie vont en bateau)

Sun 8 Jan 14:45; Sat 21 Jan 17:00

Journey to Italy (Viaggio in Italia)

Sun 8 Jan 18:20; Mon 23 Jan 14:30; Fri 27 Jan 20:50

Parasite (Gisaengchung)

Mon 9 Jan 17:50; Wed 18 Jan 17:30 BFI IMAX

The Gleaners and I (Les glaneurs et la glaneuse) + La Jetée

Wed 11 Jan 20:30; Mon 23 Jan 18:10

A Matter of Life and Death

Thu 12 Jan 20:40; Sun 22 Jan 11:30

Chungking Express (Chung Him sam lam)

Thu 12 Jan 20:45; Tue 17 Jan 20:50; Sat 21 Jan 14:15

Modern Times

Fri 13 Jan 17:45; Sun 22 Jan 13:10

A Brighter Summer Day (Guling jie shaonian sha ren shijian)

Mon 16 Jan 18:30; Sat 28 Jan 16:00

Imitation of Life

Wed 18 Jan 20:30; Wed 25 Jan 14:30; Sun 29 Jan 12:30

The Spirit of the Beehive (El espíritu de la colmena)

Thu 19 Jan 18:00; Sat 28 Jan 13:50

Sansho the Bailiff (Sansho Dayu)

Fri 20 Jan 17:45; Thu 26 Jan 17:50

Andrei Rublev

Thu 26 Jan 18:40; Sun 29 Jan 17:20

BFI SOUTHBANK

Welcome to the home of great film and TV, with three cinemas and a studio, a world-class library, regular exhibitions and a pioneering Mediatheque with 1000s of free titles for you to explore. Browse special-edition merchandise in the BFI Shop.We're also pleased to offer you a unique new space, the BFI Riverfront – with unrivalled riverside views of Waterloo Bridge and beyond, a delicious seasonal menu, plus a stylish balcony bar for cocktails or special events. Come and enjoy a pre-cinema dinner or a drink on the balcony as the sun goes down.

BECOME A BFI MEMBER

Enjoy a great package of film benefits including priority booking at BFI Southbank and BFI Festivals. Join today at bfi.org.uk/join

BFI PLAYER

We are always open online on BFI Player where you can watch the best new, cult & classic cinema on demand. Showcasing hand-picked landmark British and independent titles, films are available to watch in three distinct ways: Subscription, Rentals & Free to view.

See something different today on player.bfi.org.uk

Join the BFI mailing list for regular programme updates. Not yet registered? Create a new account at www.bfi.org.uk/signup

Programme notes and credits compiled by the BFI Documentation Unit

Notes may be edited or abridged

Questions/comments? Contact the Programme Notes team by email